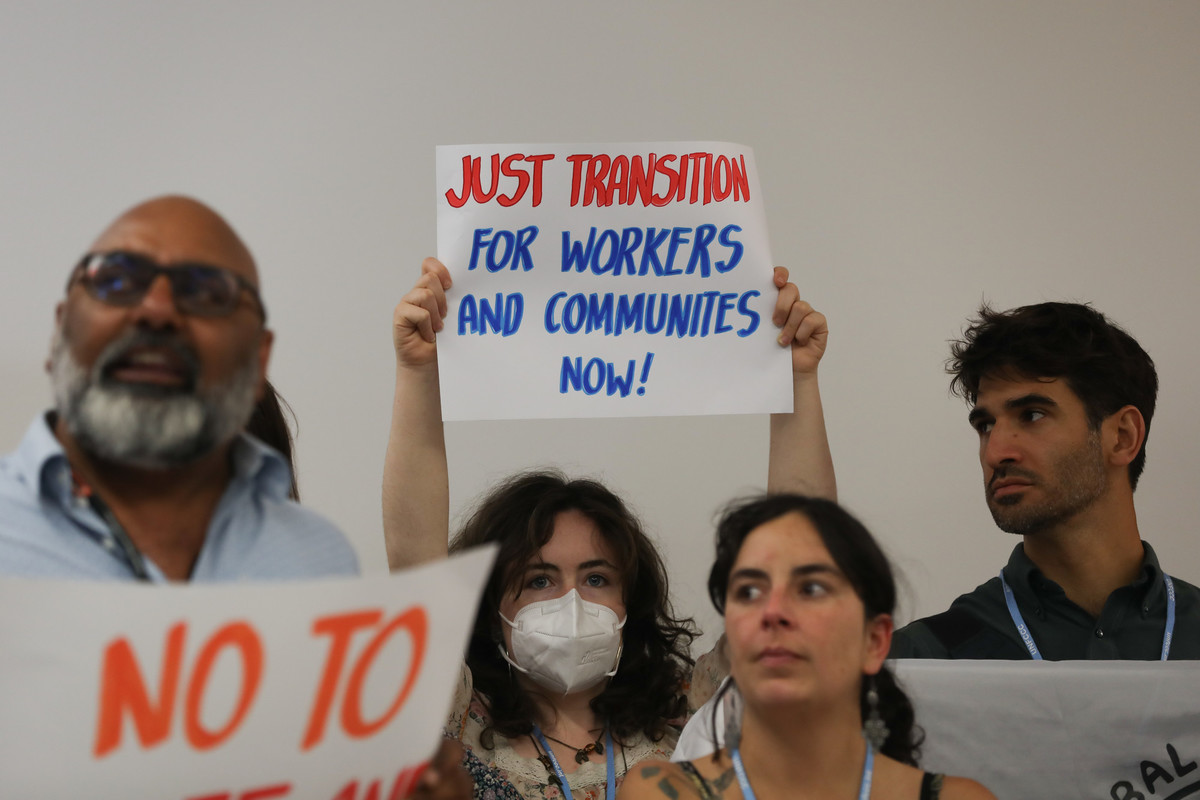

As COP 29 approaches, the Just Transition Work Programme (JTWP) finds itself at a pivotal moment. Established at COP 27 and refined at COP 28, the JTWP was launched to guide countries in creating socially equitable pathways towards a low-carbon economy, ensuring that workers, communities, and vulnerable groups are supported through this transition. However, ongoing discussions have highlighted significant differences in priorities and implementation strategies.

The First Dialogue mandated under the JTWP, which took place in June 2024 ahead of the 60th sessions of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change Subsidiary Bodies in Bonn, underscored these challenges by revealing sharp divides between developed and developing nations over the programme’s core focus and how it should unfold. Developed nations emphasised economic and job-centred aspects of just transition, while developing countries, represented by groups including the G77 and China, argued that the JTWP should encompass broader social justice and environmental considerations and pushed for a structured, action-oriented work plan. Although some procedural agreements had been reached by the time the Bonn meeting closed, many substantive issues remained unresolved, with the path forward left largely undefined.

The Second Dialogue of the JTWP, held in Sharm el-Sheikh in October, sought to build on these discussions by bringing together representatives from governments, international organisations, trade unions, and other civil society groups to explore critical themes including financial support, workforce reskilling, and social protections. Participants engaged in conversations centred around three guiding questions: how to empower all societal groups, how to secure essential resources for developing nations, and how to foster international cooperation to advance the JTWP’s goals.

What Happened at the Second Dialogue of the JTWP?

Workforce reskilling remained a central theme, though its role was viewed differently across the spectrum of participants. Representatives from developing nations, including Egypt, argued that reskilling alone will be insufficient to meet the broader needs of workers. While this contingent recognised the importance of skills development, they emphasised that workers in resource-dependent economies also require stable jobs, fair wages, and secure working conditions. A Bolivian delegate, for instance, stressed that a just transition should protect traditional ways of life, particularly those of Indigenous communities, rather than focusing solely on new skills in areas where they might not be practical. It was argued that a broader vision of just transition is needed: one that goes beyond reskilling to support established, sustainable practices in communities. On the other hand, developed countries, including the European Union and the United States, placed a strong emphasis on reskilling as being essential to economic transformation within the just transition framework. Representatives from this bloc highlighted the need to prepare workers for new roles in emerging green industries, seeing targeted workforce development as a way to align workers with changing labour market demands in a low-carbon economy.

Social protection was another significant focus of the dialogue, especially for vulnerable communities that face challenges related to rising energy costs, job losses, and economic shifts linked to climate policies. Representatives from developing countries, such as Chad, argued that social protections should not be secondary considerations but integral elements of climate policies and thus of the nationally determined contributions. Participants also called for social protections to be embedded directly into climate adaptation strategies, especially disaster risk reduction frameworks, to provide stability and resilience for workers and communities navigating the impacts of climate change and economic transitions.

Representatives from developing countries argued that social protections should not be secondary considerations but integral elements of climate policies and thus of the nationally determined contributions.

When discussing finance, representatives from the Global South stated that without reliable funding, they would be unable to meet the JTWP’s objectives. They argued that financing is crucial for social protections, workforce reskilling, and, more broadly, climate resilient development. A Colombian delegate pointed out that existing financial constraints, such as high debt burdens, make it difficult for many developing countries to fully implement their just transition goals, which calls for reform of the global financial architecture. Similarly, Igor Paunovic from United Nations Trade and Development emphasised the need for significant global investment to support equitable climate resilience, especially for vulnerable regions.

Social dialogue was recognised as fundamental to achieving a just transition. Many participants stressed that those who are most affected by the transition, such as local farmers, care workers, and workers in informal sectors, must have a central role in shaping transition policies. They argued that effective social dialogue requires both top-down and bottom-up engagement to ensure that policies reflect the real needs of communities and industries on the ground.

Finally, technology transfer and capacity-building completed the list of factors considered to be essential for a just transition. Delegates argued that equitable access to technology is not just an economic concern but a matter of social justice, enabling developing countries to actively participate in green industries. Many advocated for policies that promote open access to technology, in particular through mechanisms that facilitate technology-sharing and capacity development. Luca Lungo from the United Nations Industrial Development Organization stressed that a successful transition would require extensive deployment of clean technologies and diversification of global supply chains. Open intellectual property policies, he noted, would make it possible for a broader range of countries to benefit from and contribute to the global green economy.

Second Dialogue of the JTWP: What did participants think?

Reflections from participants of the Second Dialogue highlighted a broad range of experiences, with some optimism about the format and content of the discussions. Jazmin Burgess from C40 Cities, representing the Local Government and Municipalities Constituency, left the dialogue with a positive impression, appreciating the opportunity for observers to facilitate and thus help shape and drive the conversation. This positive perspective was echoed by Stig Svenningsen from Norway, who noted that countries share significant common ground even if they approach topics differently. The Norwegian representative praised the open sharing of experiences, adding that insights from Colombia and Bolivia on consulting local communities were interesting and contributed to a spirit of collaborative learning.

Participants from academia also voiced appreciation for the dialogue’s inclusivity. Lea Kammler from the University of Hamburg described it as fostering a space for “rich, diverse discussions.” She observed that bringing to light shared perspectives and key differences in priorities was beneficial for building a comprehensive understanding of the variety of approaches to just transition. Robert Marinkovic, representing Business and Industry NGOs, similarly felt that the dialogue was valuable and praised the sessions for highlighting solutions and offering insights into countries’ best practices. Marinkovic further appreciated the World Café structure and hybrid accessibility, which he found effective for inclusive discussion. However, he noted that some subtopics overlapped, occasionally leading to circular discussions that detracted from advancing new insights.

Patrick Rondeau, a trade union representative, expressed frustration that the dialogue felt repetitive and offered limited progress on critical issues such as labour rights, fossil fuel transition, and financing.

Meanwhile, some participants felt that certain structural limitations hindered the dialogue’s inclusivity. Sinéad Magner from the Women and Gender Constituency, attending virtually, felt that placing multiple representatives from the same constituency in identical breakout groups restricted opportunities for cross-group interaction, and that the framing of some topics was limiting the conversation. She nevertheless expressed hope that the official report from the dialogue would provide a meaningful summary and underscored the need for COP 29 to deliver an actionable just transition plan to ensure real-world impact.

Reflections also centred around the scope of the dialogue and the topics selected. Some participants felt that the chosen topics did not fully reflect developing countries’ priorities, raising questions about inclusivity in setting the agenda. Tamim Alothimin from Saudi Arabia, for example, argued that the themes selected did not align with those proposed by the G77 and China, which the group believed would have garnered broad support. Patrick Rondeau, a trade union representative, expressed frustration that the dialogue felt repetitive and offered limited progress on critical issues such as labour rights, fossil fuel transition, and financing. He further warned that without clear, actionable steps, the JTWP risks becoming a “talk shop” that lacks practical outcomes for affected workers and communities, and therefore stressed that moving from dialogue to concrete action is a priority for COP 29 to ensure the JTWP retains credibility.

Finally, many participants noted that a large number of finance negotiators attended the dialogue, highlighting the increased importance countries are attaching to the topic of funding as part of the JTWP.

COP29 and Beyond: What progress can we expect?

As COP 29 approaches, the JTWP stands at a pivotal juncture. While the specific function of these dialogues remains loosely defined, most stakeholders see them as valuable opportunities to share technical insights and discuss diverse approaches to just transition. Others, however, have expressed the hope that these dialogues will evolve beyond technical exchanges into fostering broader understanding and building a stronger foundation for the upcoming negotiations under the JTWP.

While expectations for a big JTWP breakthrough at COP 29 remain low—with many investing greater hope in COP 30 and its Brazilian presidency—participants still see COP 29 as an opportunity to address some unresolved issues and set the JTWP on a path to actionable commitments that reflect the diverse needs of all participating nations and stakeholders.

To access presentations and watch all recordings of the Second JTWP Dialogue, visit the dedicated event page here.

Simon Dünnenberger is a policy analyst and Jonas Kuehl is a policy advisor at the International Institute for Sustainable Development. They’re both members of the JET-CR Knowledge Hub editorial team.

Stay Informed and Engaged

Subscribe to the Just Energy Transition in Coal Regions Knowledge Hub Newsletter

Receive updates on just energy transition news, insights, knowledge, and events directly in your inbox.