Commentary

What Justice in Whose Just Transition? Mapping Justice Implications in Climate Action

Country:

Global,

Organisation:

Grantham Research Institute at LSE,

Decisions made about how we avoid the worst of catastrophic global climate breakdown have justice implications. This is not least due to the disproportionate impacts that climatic disruptions have on different communities across disparate global geographies, but it is also because climate change arose from a system of entrenched inequity. This critical juncture is where the concept of a just transition comes in.

Be it in the rooms of multilateral climate negotiations, national governments and legislatures or in the collective of grassroots climate advocacy, the question is not about whether we will have a just or an unjust transition. Rather, it is about how justice is contemplated, articulated, and implemented in the transition to low greenhouse gas emissions and climate-resilient development.

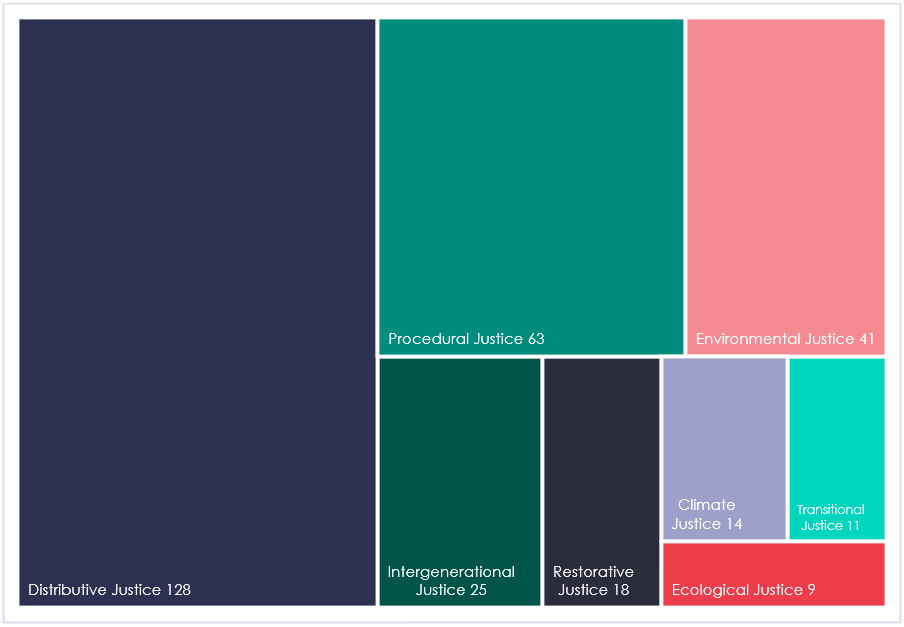

Indeed, the idea of justice can be understood differently in different contexts. This story is told by our latest empirical review of 159 policies across 61 countries and the European Union that include references to a just, fair, equitable, and inclusive transition. Even when the precise term “just transition” is not used, we see a rise in instances where the justice implications of policy measures in response to climate change are being explicitly (or often implicitly) considered (see Figure 1). However, whilst many policies mention certain types of justice, their implementation does not necessarily mean they will deliver that type of justice.

What Justice?

How justice applies to, and is perceived by, diverse stakeholders is influenced by their lived experiences and contextual realities. Our review shows that the majority of policies are focused on the concept of distributive justice, which concerns the fair distribution of risks and opportunities while being cognisant of gender, race, and class inequalities. This applies to ensuring that the economic burden of the transition is not borne by formal and informal workers in high-emitting industries or by lower-income households, consumers, or communities.

Communicating a general narrative of a “just transition” that does not account for existing injustices may weaken the transformative potential to get affected stakeholders on board.

Likewise, procedural justice has become a popular concept, wherein policies focus on the agency of affected groups in decision-making. Procedural justice ensures that the needs and priorities of the groups who are the most affected are properly captured. In addition, in a political environment in which climate disinformation is rife, procedural justice can prevent a backlash against policies that are not perceived as having been developed in a fair and inclusive way.

Figure 1. Frequency of types of justice identified across 159 national climate policies

Other types of justice—such as environmental, ecological, restorative, and transitional justice—are fundamentally geared towards redressing and repairing existing, systemic socio-environmental harms for both people and ecosystems. Not surprisingly, the level of inclusion in policies of these types of justice was low. This can be attributed to the fact that such justice typologies require policy mechanisms that are more substantially focused on transforming the existing political economic system, and the pathways to these mechanisms are less clear to mainstream policy-makers. The prevalence of one type of justice over another may also be attributed to the politicisation of justice language in distinctive policy-making environments. Communicating a general narrative of a “just transition” that does not account for existing injustices may weaken the transformative potential to get affected stakeholders on board.

What this tells us is that policy-makers should consider collecting information ex ante to identify which specific injustices need to be redressed or addressed in a given situation, before devising the policy instruments for intervention. At the same time, researchers need to continue supporting policy-makers in mapping these policy challenges and objectives in key concepts of justice, and they must bolster shared understanding in a contested and crowded international discourse. What a just transition means for each country and each sector will continue to evolve as the world transitions. There is a real danger that vulnerable stakeholders will become increasingly alienated and disengaged if just transition messaging is used improperly.

Whose Just Transition?

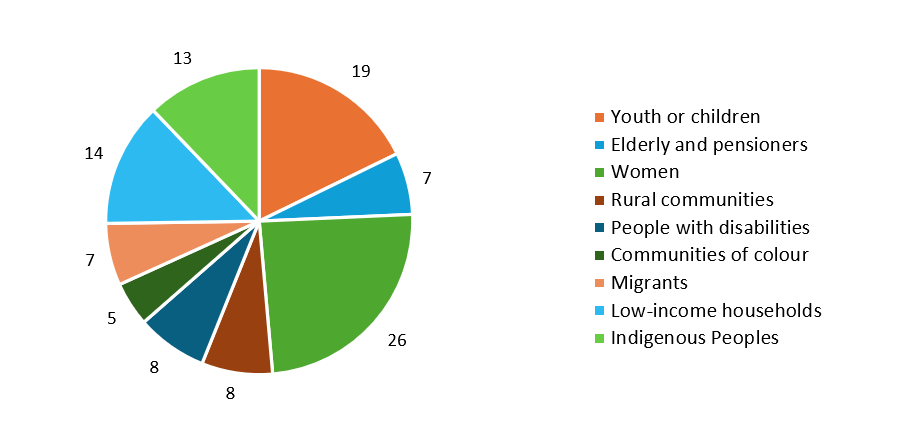

At their core, climate policies affect people and livelihoods. Born out of the trade union movement, the concept of just transition has evolved from minimising the risks to workers in the transition (as set out in the Paris Agreement) into considering a broad range of disadvantaged groups. Across the 159 policies we reviewed, 98 refer to impacts on communities, 94 address workers, and 61 refer to consumers and households (see Figure 2).

The process of identifying key stakeholder groups is indeed influenced by contextual demographic characteristics and development priorities. “Affected communities” are not homogenous, and tailoring policy interventions to support the very people who are the most acutely affected is the challenge at hand. For Türkiye, this includes providing on-site employment opportunities to climate migrants; for Bolivia, it means embracing the need to ensure Indigenous sovereignty; and for Gambia, it involves transforming social and public infrastructures (such as the transport system) to cater for a younger and more mobile population. Different countries will face distinct challenges in collecting data on how vulnerable groups are most affected by climate policy; for example, the need to understand intangible non-economic impacts associated with planned relocation. This is recognised in holistic documents like nationally determined contributions and integrated investment plans, which can help signpost the finance and other resources required to enable effective policy design and implementation.

Figure 2. Snapshot of explicit mentions of affected groups across 159 national climate policies

But what type of change does a just transition endeavour to induce? Unsurprisingly, the different interpretations of justice also manifest in the types of change that policies can bring about. Existing research has typologised a spectrum of change. At one end of this spectrum there are “status quo” and “managerial reform”: relying on voluntary, bottom-up, corporate-driven, and market-driven changes or reforms that facilitate change within the existing economic system, such as emphasising local dialogue with tripartite negotiations. At the other end are “structural reform” and “transformative change”: modifying governance structures, social ownership, or power relations, or overhauling the existing economic and political architectures and dismantling the interlinked systems of oppression. Within our review, while 107 policy documents contain some form of status quo mechanism, only six have a transformative agenda.

It goes without saying that pursuing a transformative change entails pursuing policy pathways that first redress and uproot existing structures of inequality; it requires confrontation with a swathe of new realities that may ultimately be unpalatable within our existing system of operation. There’s no single panacea policy solution to the interlinked and compounding issues of justice in climate transition. Managerial processes can be convenient (in terms of time and cost) and come up against less resistance in the face of competing interests, but we cannot afford to continue kicking the tough questions to the curb. Research institutions have a role to play in demystifying and deciphering the benefits, drawbacks, and mechanisms of implementing a more transformative approach.

Jodi-Ann Wang is a global policy analyst and Tiffanie Chan is an associate, both at the Just Transition Finance Lab, which is hosted at the Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment at the London School of Economics and Political Science. This commentary draws on a policy report published by the authors and Catherine Higham in June 2024, titled Mapping Justice in National Climate action: A Global Overview of Just Transition Policies.

Stay Informed and Engaged

Subscribe to the Just Energy Transition in Coal Regions Knowledge Hub Newsletter

Receive updates on just energy transition news, insights, knowledge, and events directly in your inbox.