Commentary

Embedding Justice into India's Sectoral Transitions

Country:

India,

Organisation:

Climate Policy Initiative,

A Historic Transition

Over the centuries, transitions in various forms have disrupted economies. Think of the shift from horse and cart to the motor car, or the replacement of manual labour with automation in factories. While these brought the benefits of increased mobility and cheaper production, they also came with downsides, such as loss of revenue and livelihoods for traditional service providers.

Another major transition is now unfolding across the globe. Carbon-intensive sectors like power generation, transportation, and industry are having to undergo a significant shift to achieve the significant decarbonisation required for net-zero greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions.

The window is rapidly closing for addressing the damage caused by centuries of GHG emissions (the stock), which is continuing to increase with ongoing emissions (the flow). Immediate action is essential.

Why a Low-Carbon Transition Alone is Not Enough

Conventional approaches to the low-carbon transition have focused on replacing existing fossil fuel technologies while neglecting the social implications. A more just approach is therefore needed to make the transition equitable, sustainable, and successful.

“A Just Transition means greening the economy in a way that is as fair and inclusive as possible to everyone concerned, creating decent work opportunities and leaving no one behind.” — International Labour Organization

The Principle of Just Transition

The principle of just transition is aligned with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), in particular the goals of decent work and economic growth (SDG 8), affordable and clean energy (SDG 7), climate action (SDG 13), and no poverty (SDG 1).

The concept emerged in the 1980s as labour movements in industrialised countries focused on worker protection while implementing environmental regulations. It is now gaining renewed focus in the context of achieving climate goals while ensuring that everyone benefits from the shift.

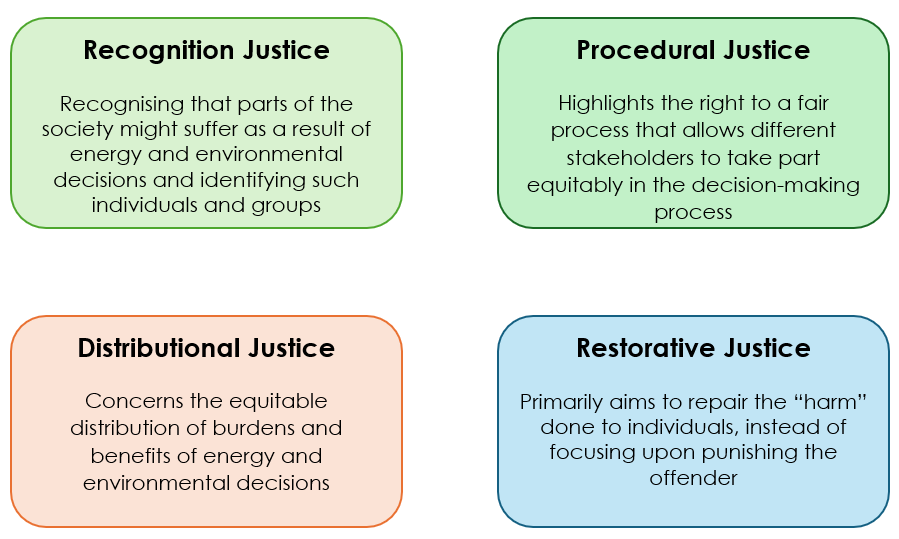

The ILO defines four key principles to guide a just transition: recognition justice, procedural justice, distributional justice, and restorative justice. By integrating these principles, countries can build a transition that is not only environmentally sound but also socially just.

In India the idea of just transition is now taking shape, and sectors are at different stages on their transition timelines. The power sector is likely to spearhead this change, given the rise in effective and affordable clean technologies paired with the sector’s high mitigation potential. By decarbonising electricity generation first, India can then provide other sectors with clean energy to reduce their own carbon footprints. This approach can allow for a more manageable and equitable transition.

A Just Transition for the Power Sector

India’s power grid has traditionally relied heavily on the country’s abundant domestic deposits of solid fossil fuels to bring electricity even to remote areas. This has provided energy security and fostered economies around fossil fuel extraction and use in mineral-rich states, but it also presents significant decarbonisation challenges. A 2023 Climate Policy Initiative (CPI) study, “Vulnerability Assessment of Mineral-Rich States to Energy Transition,” found that eastern Indian states, especially Odisha, Jharkhand, and Chhattisgarh, may face economic disruption due to both climate change and the shift to cleaner energy sources in response.

CPI’s subsequent assessment, focused on the state of Jharkhand, found that the annual economic implications could reach a total of USD 8.7 billion for stakeholders, who include public sector undertakings, the government, and employees in the formal and informal sectors. To ensure a fair shift to clean energy, a just transition plan for the power sector will require smart policies, financial resources, and creative funding options. Last but not least, skills development and reskilling programmes will be needed for the entire workforce, including contractual and indirect employees.

A Just Transition for Mobility

India’s mobility sector is on an upward trajectory and is already the third-largest market in the world. Sales of passenger and commercial vehicles are expected to rise along with economic activity. This will drive up emissions from the sector, which already constitutes 12% of India’s total emissions. Government initiatives to promote zero emission vehicles and the changing landscape for internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles are expected to spur the transition in this sector.

As per estimates, between 45% and 84% of ICE vehicle parts, primarily powertrain components, will become obsolete due to the transition, impacting the manufacturers of such components. This will likely disrupt the network of small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs) that forms the backbone of the automobile industry.

The clean energy shift will primarily involve reskilling the workforce, with a significant portion (around 16%) of ICE-related jobs potentially becoming obsolete. While the transition is expected to have a positive impact on formal jobs, a significant number of informal workers, such as roadside mechanics, could face a loss of business as the industry adapts to electric vehicles. Any just transition framework for mobility should go beyond shifting to cleaner fuels and consider reskilling for those engaged in the ICE industry so that they can take advantage of new opportunities created by clean technologies.

A Just Transition for Hard-to-Abate Industries

The industrial sector presents the most complex transition, because emissions from core industries such as steel and cement are especially challenging to abate. India’s demand for these essential materials is expected to surge to three or four times the demand of today by 2050. This is being fuelled by ambitious government infrastructure initiatives including Housing for All, which aims to provide 20 million affordable homes, and projects in the National Infrastructure Pipeline.

The steel and cement industries are already taking steps to reduce their carbon footprints by using available technologies. A steeper decline in emissions is expected in the future as greener technologies become commercially viable and green hydrogen becomes more affordable. While larger players are better placed to handle this transition, SMEs, which constitute 33%–35% of India’s crude steel capacity, will be more impacted owing to their constrained capital and differing priorities.

Similarly, the workforce employed in the industry supply chain, particularly in associated SMEs, will be vulnerable to job losses. By their very nature, SMEs are labour intensive, have a primarily informal workforce, and have limited financial resources. Thus, just transition plans for hard-to-abate sectors should focus on these SMEs and their workforce.

Required Action

The action to enable a just transition needs to be cohesive, with decisive contributions from all quarters. Different sections of society can consider the following actions.

Government institutions:

- Embedding just transition considerations into policies and transition planning.

- Building the capacity of government institutions, industries, and workforces to facilitate the transition.

Industry:

- Investing in greener technologies

- Reskilling the workforce to use those technologies.

Financial institutions:

- Providing low-cost finance via innovative and customised solutions (such as blended finance) to help impacted sectors adapt to the transition.

Research institutions:

- Publishing quality research reports that quantify the costs and opportunities of a just transition led by green growth.

- Facilitating discussions among key stakeholders on just transition principles, strategy, and financing.

Philanthropic institutions and individuals:

- Using philanthropic money to catalyse and de-risk low-carbon investment.

- Enabling the capacity building of institutions involved in the transition and reskilling the impacted workforce.

The actors mentioned above bring unique expertise and have differing expectations of what deploying their resources will achieve. A mechanism needs to be devised that enables them to work in cohesion while fulfilling their expectations and accelerating the just transition in specific sectors.

Md Tariq Habib is a Senior Analyst, Saarthak Khurana a Senior Manager, and Vivek Sen the Acting Director for Climate Policy Initiative (CPI) India, a research and advisory institution, working on climate finance and low carbon transition.

Stay Informed and Engaged

Subscribe to the Just Energy Transition in Coal Regions Knowledge Hub Newsletter

Receive updates on just energy transition news, insights, knowledge, and events directly in your inbox.