Commentary

Op-ed: Why Planning Frameworks are Essential for a Just Transition

The just transition calls for navigating complex pathways to find a balance between often seemingly competing interests. Planning frameworks can help.

Organisation:

The Carbon Trust,

The importance of a just transition in the move towards a decarbonised economy cannot be overstated. Without a clear commitment to engage affected stakeholders and effectively manage the socio-economic impacts of the transition, the urgently needed shift would be delayed or derailed altogether due to local dissent or political fallout.

Striking the right balance between taking urgent climate action and mitigating the negative social consequences (such as job losses, increased energy prices, and unequal distribution of clean technologies) is hugely complex, and there is no “one size fits all” solution.

The impacts of a net-zero transition will differ between countries, sectors, regions, and even companies and assets, so what is deemed to be “fair” or “equitable” will differ, too. Yet dedicated frameworks for planning for a just transition can help decision-makers to navigate complex trade-offs by integrating core social justice principles and best practice guidance.

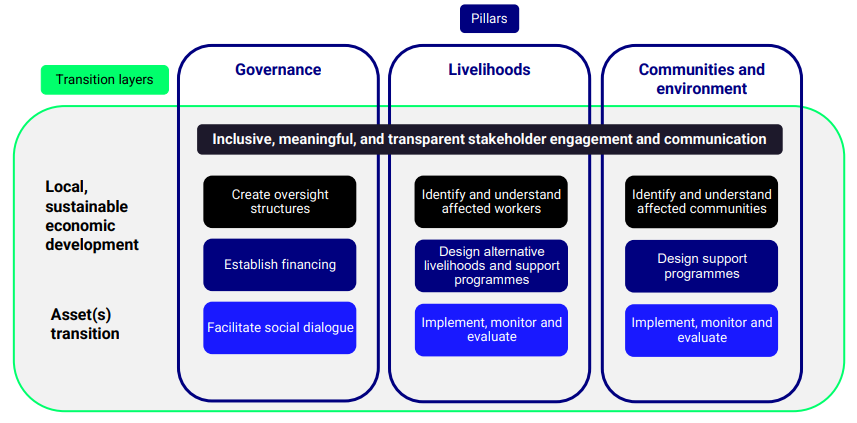

The Carbon Trust’s ‘Just transition planning framework’ (JTPF) was developed as part of efforts to support the Odisha State Government in India to navigate these complexities of moving away from dependencies on coal. Based on comprehensive reviews of global case studies of transition management, the framework offers tools and guidance at different stages of the planning process across three key pillars:

- Governance: Guidance on establishing dedicated institutions, structures, and funding processes to drive and be accountable for the just transition. This can include forums to facilitate social dialogue, and technical advisory groups.

- Livelihoods: Guidance on types of support for impacted parties, and tools to assess impacts on direct, indirect, and induced employment. It features practical tools— to examine the gaps between the skills and knowledge of fossil fuel workers and those required in clean energy.

- Community and environment: Tools to assess social, economic, and environmental risks to the wider community, and policy and programme options to help mitigate these risks. Options include investing in community ownership of renewable energy projects to help provide tangible benefits to the community and maintain a sense of cohesion.

Figure 1. The JTPF sets out the key pillars and processes for consideration in planning for an energy transition at different scales: the asset level and the wider regional level.

Odisha, a state in India, was used as a case study to test the framework because of the size of the state’s coal fleet and India’s relevance in the global challenge of transitioning from coal to clean energy. The intention was to provide a high-level, practical example of the framework’s application and demonstrate that it could be used to provide insights and support decision-making around complex energy transitions. In developing recommendations for the drafting of a just transition plan for Odisha’s coal–fired power plants, several key lessons were learned:

Be ambitious but realistic about scope (don’t let perfect be the enemy of the good). Limited resources mean difficult decisions about where these are allocated; not everyone who has an interest can be engaged or provided with support. A critical early step of applying the framework is to set a reasonable and realistic scope and ambition: finding a balance between shallow and wide support for a broad range of stakeholder groups, and narrow and deep support for those who are most affected. In Odisha, impacted stakeholders range from direct workers, adjacent communities, and businesses and individuals along the coal value chain (including the mining and transportation of coal) through to energy consumers in the state who may be affected by changes in access to and prices of electricity should coal-fired power plants be decommissioned. Early, proactive dialogue will support prioritising impacted groups and setting a realistic scope for support, while avoiding slowing the transition too much.

Limited data and representation of some impacted groups can pose a significant challenge to understanding the risks. The taxonomy of potentially impacted stakeholder groups set out in the framework goes some way to identifying social risks, but these are highly dependent on context. In Odisha, the significant informal sector and contracted workers are at risk of being overlooked in transition planning processes. Limited data about how many people work across the coal value chain and what their roles involve risks the impacts on these groups not being well understood and support not being provided. In contrast to many direct employees of coal-fired power plants, these groups tend not to be unionised. Alongside early, proactive, and diverse engagement, decision-makers need to undertake socio-economic impact assessments to better understand the risks and impacts.

Creating new, green jobs is unlikely to be enough. The framework identifies a range of policy support options for impacted livelihoods. Support measures for workers need to go beyond skills development and retraining for workers to consider the nature, timing, location, and security of the roles being created in new, green industries. For instance, although Odisha plans to invest in setting up 17,000 megawatts of solar capacity, most of the employment opportunities are likely to be short term or require high levels of qualifications (or both). They may also not be in the same locale as a coal-fired power plant being decommissioned. Support policies should be coordinated with other education, training, and industrial development policies so that investment in jobs and training benefits those who are most at risk.

Prioritise building community resilience with holistic, long-term investments. As far as is feasible, just transition planning should seek to enhance community resilience and regional revitalisation through sustainable economic development and diversification, as well as investments in socio-cultural and human capital. The coal industry has a long history in Odisha, and it has probably played an important role in shaping community identity and building social cohesion. Alongside investing in alternative energy sources and alternative industries to diversify local economies, policy-makers should consider investing in cultural assets, education, and community infrastructure to contribute to social as well as economic resilience.

Kate Hooper

Based in London, UK, Kate is a senior manager and the just and inclusive transitions lead at the Carbon Trust. She has been working at the intersection of energy transitions and social inclusion for almost 10 years and has experience working across coal transitions, low carbon transport, energy efficiency, sustainable finance, and renewable energy. Kate has previously worked as a researcher at the Australian National University and as a project finance analyst for a renewables company in Australia.

About the Carbon Trust

The Carbon Trust is a global climate consultancy driven by the mission to accelerate the move to a decarbonised future. Climate pioneers for over 20 years, it partners with businesses, governments, and financial institutions to drive positive climate action. From strategic planning and target setting to implementation and communication, the Carbon Trust turns ambition into impact. To date, its 400 experts have helped set over 200 science-based targets and guided more than 3,000 organisations and cities across five continents on their route to net-zero.

Stay Informed and Engaged

Subscribe to the Just Energy Transition in Coal Regions Knowledge Hub Newsletter

Receive updates on just energy transition news, insights, knowledge, and events directly in your inbox.