At the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) COP 28, countries reached a historic international agreement to transition “away from fossil fuels in energy systems, in a just, orderly and equitable manner” in line with 1.5°C pathways. This transition will require a significant reduction in coal use and extraction, with no room for new coal mines. While much focus has been placed on just transitions from coal to renewables in electricity production, less attention has been given to coal extraction. As a result, hundreds of new coal mines are still being planned and countries are set to produce more than four times the amount of coal than would be compatible with 1.5°C pathways. This imbalance risks disorganised transitions in coal-producing countries, which, as shown by previous coal transitions, could result in significant economic and social hardship.

These experiences show that transitioning away from fossil fuels requires more than decarbonising energy; it demands broader economic and non-economic policy measures to address the multi-faceted role of fossil fuels in national and regional economic activity. However, there is no “one size fits all” policy mix for achieving this transition, and policy interventions must be tailored to each country. The Coal Transitions Vulnerability Index (COTRAVI) is a new tool for identifying and understanding the vulnerabilities of coal-producing countries and for shedding light on how appropriate policy mixes can be developed through such understanding.

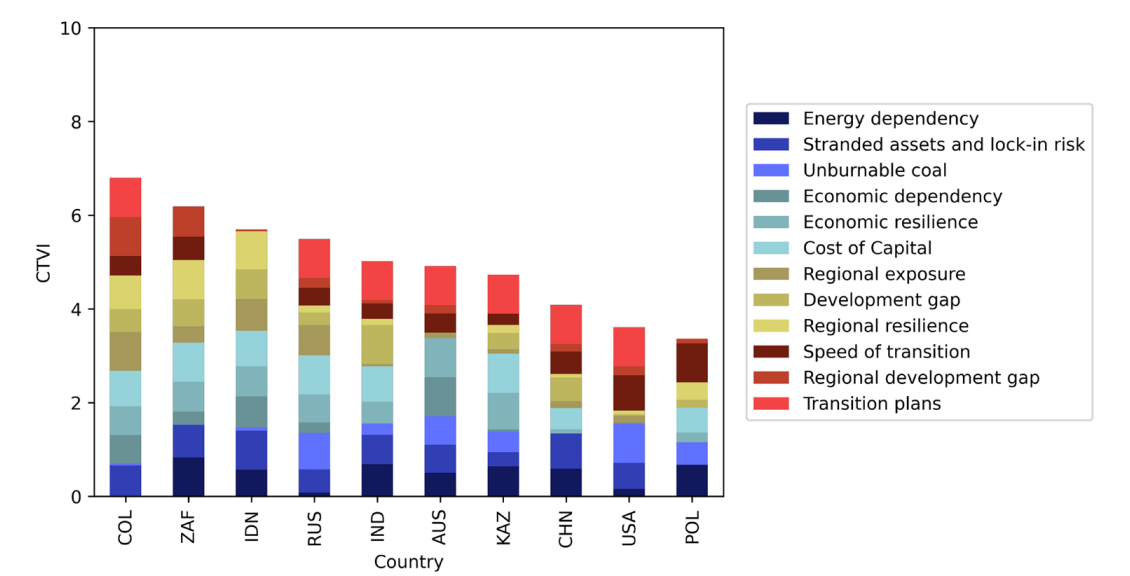

The index captures and compares the vulnerabilities of coal-producing nations by examining 12 indicators measuring the exposure to transition risk and the ability to cope with the transition. The indicators cover both national-level factors (e.g., the reserves-to-production ratio) for the 10 largest coal-producing countries of the world, where over 85% of global coal production is located and subnational-level factors (e.g., average share of coal in regional GDP) for 30 coal-producing regions that concentrate over 70% of the total national coal production for each of the top 10 producers. Figure 1 presents the results of the COTRAVI using 2019 data, with countries shown in descending order from high to low vulnerability.

The results of the COTRAVI highlight several key insights. First, while just transition plans play a crucial role in enhancing countries’ ability to cope with the transition away from coal, most coal-producing countries still have not developed such plans, which puts them in a vulnerable position when faced with the challenges of managing a decline in coal production. This point is well illustrated by the case of Colombia, the most vulnerable country according to the index, which only started to work on a just transition roadmap after the unexpected stranding of two large coal mines, representing one fifth of total national production, in 2021.

Second, countries with high vulnerability levels are concentrated in the Global South, so the high cost of capital and high economic dependency are key challenges for a just transition away from coal in those countries, and they require international support to manage the transition effectively. Emerging international support initiatives aiming to support some of these countries in their transition efforts, such as the Just Energy Transition Partnerships for South Africa and Indonesia, are first steps in this direction. It is too early to assess the effectiveness of these initiatives in delivering a just transition; however, some good practices and shortcomings of existing initiatives can inform the design and implementation of similar future instruments.

Given that global coal supply, unlike coal demand, is concentrated in a handful of large producers, bold actions in key producing countries could significantly accelerate global coal phase-out.

Third, including regional indicators (i.e., remoteness in relation to economic centres, regional development gaps, and contribution of the mining sector to regional GDP) in the COTRAVI reveals significant variations in vulnerability within countries. This emphasises the importance of considering the socio-economic profile of each region when designing transition-related policy interventions at the national and subnational level. For instance, transition planning in Indonesia should be approached differently in East Kalimantan and South Kalimantan, with economic diversification efforts more concentrated in East Kalimantan, which is more than twice as economically dependent on the mining sector than South Kalimantan is (45% versus 19% of regional GDP, respectively).

The COTRAVI adds to the long list of tools and toolboxes that have been developed to help navigate the complexities of coal transitions and guide efforts towards a just and sustainable transition away from coal on a global scale. Given that global coal supply, unlike coal demand, is concentrated in a handful of large producers, bold actions in key producing countries could significantly accelerate global coal phase-out. However, considering the scale of the transition challenges in these countries, innovative policy initiatives and support instruments will be required and must be tailored to the specific needs of coal-dependent countries. The COTRAVI can provide guidance on these specific needs to ensure a just transition for communities, workers, and future generations in these countries.

An initial list of measures that could increase or reduce vulnerability in coal-producing countries according to their specific vulnerability profile is provided in the COTRAVI paper (Table 4) on an exploratory basis. These include coal-mine moratoria, strengthening regulations on mine closures, and creating macroeconomic stabilisation funds, among others. Here, it is important to note that when designing and testing such initiatives and instruments, lessons learned from the implementation of emerging initiatives for the financing of coal phase-out, both nationally and internationally, should be considered to avoid unintended adverse impacts (e.g., perverse incentives). Similarly, findings and learnings from civil society-based networks, exchange platforms, and initiatives around just transition should be considered, if a global just transition for communities, workers, and future generations is to be achieved.

Paola Andrea Yanguas served as academic coordinator of the Transnational Centre for Just Transitions in Energy, Climate & Sustainability (TRAJECTS) until 2023 and joined IISD as a policy advisor in the Energy Team in 2024.

Stay Informed and Engaged

Subscribe to the Just Energy Transition in Coal Regions Knowledge Hub Newsletter

Receive updates on just energy transition news, insights, knowledge, and events directly in your inbox.